Professor Karl Zimmerer returned from sabbatical at France’s Montpellier Advanced Knowledge Institute on Transitions (MAK’IT) where he addressed concerns of food biodiversity amidst global changes. At MAK’IT, Zimmerer delved into the ties between human activities, environmental shifts, and agriculture. His research, influenced by his grandparents’ culinary journey from Eastern Europe, aimed to address the growing trend of dietary simplification in resource-limited areas. With new insights ready to be shared with the academic community at Penn State and beyond, Zimmerer’s findings offer a new perspective on sustainable development and food systems.

Professor Karl Zimmerer returned from sabbatical at France’s Montpellier Advanced Knowledge Institute on Transitions (MAK’IT) where he addressed concerns of food biodiversity amidst global changes. At MAK’IT, Zimmerer delved into the ties between human activities, environmental shifts, and agriculture. His research, influenced by his grandparents’ culinary journey from Eastern Europe, aimed to address the growing trend of dietary simplification in resource-limited areas. With new insights ready to be shared with the academic community at Penn State and beyond, Zimmerer’s findings offer a new perspective on sustainable development and food systems.

Karl Zimmerer, a professor of geography, had what he said was a “transformative” sabbatical at the Montpellier Advanced Knowledge Institute on Transitions (MAK’IT) in Montpellier, France. Zimmerer applied and was accepted as a visiting scientist with MAK’IT, renowned as a global center of excellence for his research area, at the University of Montpellier.

The MAK’IT program, which recognized Zimmerer’s ongoing collaborations at the Center for Functional and Evolutionary Ecology and the Diversity and Dynamics of Society and Environment group, pursues sustainable development goals through focus on the science-policy interface of food, environment and health. Zimmerer, who also is affiliated with Penn State’s ecology and rural sociology programs, expressed his excitement about the opportunity to immerse himself in a vibrant research community with other visiting international experts.

“I was thrilled because this is the global center for the kind of research, scholarship, and science-policy advocacy that I do, and it’s very connected to influential policy debates and decision-making worldwide,” Zimmerer said. “The cohort of other visiting researchers that I am with is wonderfully diverse. I am constantly getting to present and discuss cutting-edge sustainability research with people in other fields and from other cultures.”

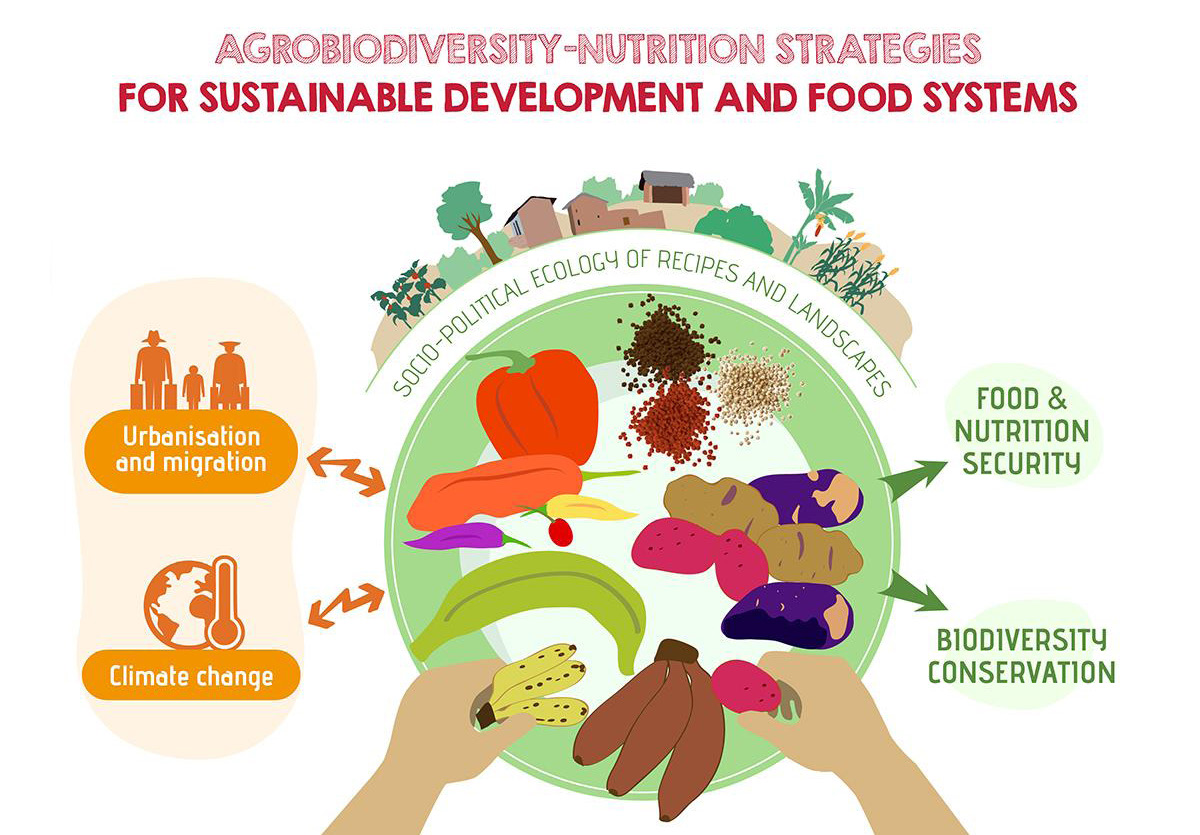

Zimmerer’s research centers on the interplay between human activities and the environment, particularly in relation to the biodiversity of food and agriculture amid rapid global changes. He has dedicated four decades to studying people and their food biodiversity in relation to changing environments and landscapes, livelihoods and sociocultural conditions worldwide. During his sabbatical, he said, he expanded his ongoing research activities and collaborations in the Western Mediterranean, especially in Spain and France, which stands out as a region emblematic of the interplay of this biodiversity and rapid changes.

In an ongoing six-year project funded through the Carasso and McKnight Foundations, Zimmerer and his collaborators from the University of Michigan and several institutions in Peru have compiled a comprehensive database of 1,200 recipes from Peru. Through rigorous analysis, they are exploring the associations between food diversity, urbanization, and migration, ultimately seeking to inform science-policy strategies to promote healthier and more sustainable food systems. Zimmerer’s sabbatical was an opportunity to test new theoretical models while integrating trips for field research and community engagement, he said.

“Diversity in our diets is not only crucial for human nutrition and well-being but also essential for maintaining healthy and resilient landscapes,” said Zimmerer. “Our landscapes need biodiversity to combat pests and diseases, maintain soil health and use water efficiently.”

“Diversity in our diets is not only crucial for human nutrition and well-being but also essential for maintaining healthy and resilient landscapes,” said Zimmerer. “Our landscapes need biodiversity to combat pests and diseases, maintain soil health and use water efficiently.”

Moreover, Zimmerer said, his research on urbanization and migration effects delves into contextual factors, such as gender, place, and generational differences, that further influence food diversity. His approach recognizes the significance of social and cultural aspects in shaping food choices and their implications for diverse populations, he explained.

Reflecting on his inspiration for this research, Zimmerer spoke fondly of his immigrant grandparents who hailed from the border of what is now Poland and Ukraine. Their journey and cultural traditions continue to influence his work, he said.

“They brought their foodways and recipes, and they’ve always been an inspiration in my life,” he said. “Their experiences motivate me to explore how we can navigate and make positive changes for people experiencing challenges today, such as immigrants and refugees.”

During his sabbatical, Zimmerer said he engaged in collaborative efforts with fellow interdisciplinary researchers, leading to a pair of new publications in the journals of Agricultural Systems and Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene. The supportive Montpellier research community played a crucial role in enriching the interdisciplinarity of his experience, he added.

Having embraced the immersive experience of living and working in France on sabbatical, Zimmerer said he relished the opportunity to refresh his French language skills and immerse himself in the rich cultural heritage of the region. He also explored French cuisine and reignited his passion for playing badminton.

Zimmerer said he anticipates sharing the knowledge and experiences of his sabbatical with colleagues, students, and practitioner communities at Penn State and the places where he is researching. He intends to integrate his findings into his new teaching and research, as well as with science-policy groups, he said, and hopes this work will inspire current and future generations of geographers, interdisciplinary researchers and policymakers, and community food activists to investigate and support the intricate connections between environment, society, and food biodiversity.

“Most of the world’s food systems are becoming more and more biologically simplified, so that about two-thirds of the world’s food comes from three or four major crops,” said Zimmerer. “This dietary simplification is a concern, particularly in areas with limited resources and high poverty levels.”